|

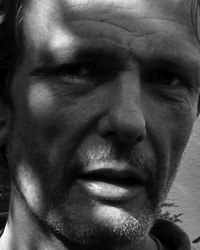

Richard Gwyn |

|

No. 81 / Julio-agosto 2015 |

| Richard Gwyn (Traducciones de Jorge Fondebrider) Richard Gwyn (Pontypool, Gales, 1956). Poeta, narrador, ensayista y traductor, realizó estudios en antropología en la London School For Economics, al tiempo que participaba como poeta en conciertos de punk a fines de los años 70. Interrumpidos sus estudios, trabajó como aserrador, publicitario y, luego de sufrir un accidente laboral, como lechero. Posteriormente se mudó a Creta, donde realizó distintos trabajos antes de emprender una vida de vagabundaje alrededor del Mediterráneo, que duró 9 años. Vuelto a Gales, estudió lingüística y, luego de doctorarse, ganó la cátedra de Literatura Inglesa de la Univerisdad de Cardiff, donde dirige la maestría en Escritura Creativa y enseña. Su poesía incluye One night in Icarus Street y Stone dog, flower red/Gos de pedra flor vermella (ambos de 1995), Walking on Bones (2000), Being in Water (2001) y Sad Giraffe Café (2010), los cuales fueron parcialmente traducidos al castellano por Jorge Fondebrider, quien además tradujo The Vagabond’s Breakfast, una memoir que le valió a Gwyn el premio a la mejor obra de no ficción publidada en Gales en 2012. Su primera novela, The Colour of a Dog Running Away (2005), fue publicada en el Reino Unido y traducida a varios idiomas. The Names I meet them in transit, in cheerless bars or dosshouses, on canal walkways, in overgrown cemeteries. Twitchy, sweating males; women following a dress code from a fictional culture. Sunstreaked, matted locks, weeks unwashed; army vests, cargo pants, pockets stuffed with dope and string, pebbles, seaweed, chewing gum; mouths poised in circumvention, never prone to the least promiscuous truth-telling. Waiting for a dead dog alibi, waiting, always waiting for drug deals never actioned. At Saloniki station I watch them swigging wine from plastic flagons; bodies crowd the shiny marble floor. And later, at the platform bar, there’s one customer, left ear missing, scrawny mongrel on a string. Talks of chicks messing with his head. And without warning slides from his stool like a sack of pans and comes to earth, legs splayed, good ear glued to the ground, muttering names: Ananke, Mnemosyne, Antigone. Los nombres Me los encuentro en tránsito, en bares sombríos o albergues, en pasarelas de canales, en cementerios abandonados. Hombres nerviosos, transpirados; mujeres que siguen un código de etiqueta propio de una cultura ficticia. Con rastas desteñidas, apelmazadas, sin lavarse durante semanas; con camisetas del ejército, pantalones cargo, bolsillos repletos de droga y cuerda, piedras, algas, chicles; bocas preparadas para escaparse, jamás dispuestas a la menor promiscua sinceridad. Esperando la coartada de un perro muerto esperando, siempre esperando la compra de drogas nunca tramada. En la estación de Salónica los observo beber vino de a tragos de jarras de plástico; cuerpos amontonados sobre el brillante mármol del piso. Y luego, en el bar de la plataforma, hay un tipo al que le falta la oreja izquierda, con un perro escuálido atado de una cuerda. Habla de chicas que lo confunden. Y sin advertencia alguna se desliza de su taburete como una bolsa de papas y llega al piso, las piernas separadas, la oreja buena pegada a la tierra, murmurando nombres: Ananke, Mnemosyna, Antígona. Episodic insomnia Every night for a month he wakes at a fixed time between three and four, perplexed by the routes he took around the eastern Mediterranean years ago, following sea-tracks or mountain paths or those alleyways between tall decrepit buildings that hide or reveal a dome or minaret, glimpsing moments of a half-remembered journey. Or else he is mistaken, and it is not the journey that wakes him but the need to write about it, and his alarum is this hypnopompic camel, trotting over memory’s garbage tip: intransigent, determined. How is it that we reach that state in which the thing remembered merges with its remembering, the act of writing with the object of that need to tell and tell? And so he wakes again at a quarter to four, another dream-journey nudging him tetchily into wakefulness like a creature in search of its soul, and this time he is peering from a terrace on the milky heights at Galata, or else gazing eastward from the battlements at Rhodes, and wondering whether he has always confused the journey with the writing of it, whether the two things have finally become one. Insomnio episódico Cada noche, durante un mes, se despierta a la misma hora entre las tres y las cuatro, perplejo por las rutas que tomó hace años por el Mediterráneo oriental atrás, siguiendo caminos marítimos, o pasos de montaña, o esos callejones que hay entre edificios altos y decrépitos que esconden o revelan una cúpula o minarete, momentos atisbados de un viaje a medias recordado. O puede que se equivoque, y no es el viaje lo que lo despierta, sino la necesidad de escribir sobre éste, y su disparador es ese camello hipnopómpico, que trota sobre el basurero de la memoria: intransigente, resuelto. ¿Cómo es que alcanzamos el estado en el que la cosa recordada se mezcla con su recuerdo, el acto de escribir con el objeto de esa necesidad de contar y contar? Y entonces vuelve a despertarse a las cuatro menos cuarto, otro viaje soñado que lo impulsa malhumoradamente a desvelarse como una criatura que busca su alma, y esta vez mira desde una terraza sobre las blancas alturas de Gálata, o también observando en dirección al este desde las almenas de Rodas, y preguntándose si siempre ha confundido el viaje con escribir sobre el viaje, si ambas cosas finalmente se han convertido en una. Cities and Memories Variations on a theme by Calvino When a man drives a long time through wild regions, his imagination begins to wander. No, that’s not right. Try again. When a man drives across the last continent at night, from south to north, he must pass the mountain plateau of Omalos. Oh please, not that. Once more? When a man drives a long time across the dry plains of Thrace, he begins to wonder at the migrations that have marked this wretched zone. Turks, Bulgarians and Greeks, with varieties of cruelty and facial hair, wielding curved swords at one another’s throats for centuries. Forced expulsions, exterminations, and the underlying terror that who you are, or who they say you are, is all a terrible mistake, merely circumstantial. And why, for that matter, are you not someone else? If only – you conjecture – I were someone else, and belonged to a different tribe, had a different shaped moustache or nose, the smallest detail of appearance and accent that matters beyond the value of a life. The Levant’s legacy, never yet resolved: Greek, Turk, Arab, Jew. I want to be friends with everyone, and yet know I must have enemies too, if only in order to maintain my friendships. What kind of crazy thinking is that? Salonika, Smyrna, Alexandria, Beirut. We edge into new territories, in which boundaries are differently conceived and yet still intact. How do we progress from here, to the next point, the next dubious epiphany? I feel at once as though we have been witness to a slow disembowelling, over many centuries. Ciudades y recuerdos Variaciones sobre un tema de Calvino Cuando un hombre conduce por un buen rato por regiones salvajes, su imaginación comienza a divagar. No, eso no es correcto. Inténtalo de nuevo. Cuando un hombre conduce a través del último continente por la noche, del sur al norte, tiene que pasar la meseta montañosa de Omalos. Oh, por favor, eso no. ¿De nuevo? Cuando un hombre conduce un buen rato a través de las secas planicies de Tracia, comienza a preguntarse por las migraciones que han marcado esa región desdichada. Turcos, búlgaros y griegos, con variedades de crueldad y pelo facial, blandiendo mutuamente espadas curvas contra las gargantas de los otros durante siglos. Expulsiones forzadas, exterminios y el terror subyacente de que el que eres, o el que dicen que eres, sea un error terrible, meramente circunstancial. ¿Y por qué, entonces, no eres otro? Si fuera otro –conjeturas– y perteneciera a una tribu diferente, tendría un bigote o una nariz con otra forma, el menor detalle de apariencia y el acento que importa más allá del valor de una vida. El legado del Levante, todavía sin resolver: griego, turco, árabe, judío. Quiero ser amigo de todos y, sin embargo, sé que también tengo que tener enemigos, aunque más no sea para mantener mis amistades. ¿Qué clase de locura es ésta? Salónica, Esmirna, Alejandría, Beirut. Nos adentramos en nuevos territorios, en los cuales los límites están concebidos de manera distinta y, sin embargo, siguen intactos. ¿Cómo avanzamos desde aquí al próximo punto, a la próxima y dudosa epifanía? Siento de inmediato como si hubiésemos presenciado un lento destripamiento, que tuvo lugar a lo largo de muchos siglos. Peter and the Ants On the island’s old capital I lived next door to Peter. Most mornings we would sit drinking in his shack, saying little, while he studied the behaviour of ants on the dirt floor. He told me he was training them. I dismissed this as the raving of an incorrigible inebriate. He was a perennial source of improbable explanations, fantastical stories. He tottered along the border between the familiar world and another, more tenuous reality. Then one day Peter came banging on my door, insisted that I follow him to his tiny hovel, with its whitewashed walls and corrugated tin roof. He left the door ajar, to let the light in. Thousands of ants were lined up on the floor, in perfect formation, as though practising drill. On close inspection I could see that they were marking time, beating out a rhythm with their tiny feet. Row upon row; column upon column. Now watch, said Peter. Just watch. Peter y las hormigas En la vieja capital de la isla, yo vivía al lado de lo de Peter. Muchas mañanas nos sentábamos a beber en su casucha, hablando poco, mientras él estudiaba el comportamiento de las hormigas en el piso de tierra. Me dijo que estaba entrenándolas. Desestimé la cuestión considerándola chifladura de un ebrio incorregible. Era una fuente perenne de explicaciones improbables, cuentos fantásticos. Se tambaleaba por el borde del mundo familiar y de otra realidad más tenue. Y un día Peter vino a golpear a mi puerta y me insistió para que lo siguiera a su minúsculo cuchitril, de paredes blanqueadas y techo de chapa corrugada. Entreabrió la puerta para dejar que entrara la luz. Había miles de hormigas alineadas en el piso, en perfecta formación, como si estuvieran haciendo un ejercicio de práctica. Al mirar de cerca, pude ver que estaban marcando el paso, moviéndose rítmicamente con sus diminutas patas. Fila tras fila, columna tras columna. Ahora observa, dijo Peter. Solo observa. |

Leer “Introducción a la poesía de Gales”, Pedro Serrano, Periódico de Poesía núm. 77 Leer a Richard Gwyn sobre David Greenslade, Periódico de Poesía núm. 78 |

|

|